Banking and Morality: 100% Reserve versus "Fractional" Reserves

October 20, 2008 by Paul McKeever

In written pieces (see here, here, and here, for examples) and in videos, I have advocated a 100% reserve requirement for banks. I am hardly original in doing so. A 100% reserve was advocated by the Chicago professors who advised Roosevelt during the banking crisis of the 1930s (see Ronnie Phillip’s excellent article on the topic); it is and was advocated by several economists of the Austrian school, including, according to Gary North, Ludwig von Mises; it was most famously advocated by famous American economist Irving Fisher; it was even advocated by Milton Friedman before he concluded that it was politically difficult to achieve, and settled, instead, for monetarism (see his “A Program for Monetary Stability). However, unlike some of those economists, my reasons are founded on ethics, not on economics: a 100% reserve prevents inflation of the money supply and, thereby, prevents non-consensual wealth redistribution.

In written pieces (see here, here, and here, for examples) and in videos, I have advocated a 100% reserve requirement for banks. I am hardly original in doing so. A 100% reserve was advocated by the Chicago professors who advised Roosevelt during the banking crisis of the 1930s (see Ronnie Phillip’s excellent article on the topic); it is and was advocated by several economists of the Austrian school, including, according to Gary North, Ludwig von Mises; it was most famously advocated by famous American economist Irving Fisher; it was even advocated by Milton Friedman before he concluded that it was politically difficult to achieve, and settled, instead, for monetarism (see his “A Program for Monetary Stability). However, unlike some of those economists, my reasons are founded on ethics, not on economics: a 100% reserve prevents inflation of the money supply and, thereby, prevents non-consensual wealth redistribution.

Over at YouTube, a vlogger by the name PortfolioManager1987 has posted a video singing the praises of our current, fractional reserve, system of banking. He suggests that Objectivists, like myself, are wrong to support a 100% reserve, and suggests we embrace the current fractional reserve system.

I’ve heard and considered the arguments he makes many times in the past, because they are the same ones used by libertarian advocates of “free banking”. With all due respect to PortfolioManager1987, he – like the others – (a) appears not to understand 100% reserve banking, and (b) misses what it is about fractional reserve banking that makes it immoral. He having mentioned me by name in his video, I responded to his video as follows:

I advocate a 100% reserve system. You appear to suggest that, with a 100% reserve, banks do not create credit, that banks do not lend out credit for productive investment, and that banks do not receive interest. None of those things are true in a 100% reserve system. In a 100% reserve system, banks create $1 of credit for each dollar of currency, and they lend out that dollar of credit for interest.

In a 100% reserve system, the depositor is paid interest on his deposit if he agrees to let the bank use his money. To do that, he agrees that, for a fixed period of time (e.g., one year), he will have no right to withdraw the money that is being loaned out. That system allows the bank to create only $1 of credit for each dollar on “time deposit” (e.g., GICs).

In contrast, in a fractional reserve system, the depositor retains the right to withdraw all of the money he has on deposit with the bank. The bank then creates more than $1 of credit for each dollar on deposit: $1 for the depositor, and some fraction of $1 (e.g., 95 cents) that is loaned out to a borrower. For example, with a 5% reserve, the depositor holds $1 of credit, the bank holds $1 of currency (e.g., a $1 central bank note), and a borrower holds 95 cents in credit. The same dollar, in other words, is simultaneously owed to the original depositor, and to anyone who holds the 95 cents of credit. Usually, that 95 cents gets deposited in another bank and, when that happens, it is treated the same as currency. The receiving bank issues a 95 cent credit to the depositor, holds 95 cents of credit issued by the first bank, and issues approximately 90 cents in additional credit to another borrower. The process continues as such. Ultimately, with a 5% reserve, the first $1 of currency results in the creation of about $19 in credit ($19 in credit if one excludes from the count the amounts issued by a given bank to a given depositor). With zero reserve requirement – as in Canada – there is no legal limit to the number of dollars that can be created and loaned out by a bank.

The issue is not fraud. The issue is theft. From the perspective of a saver or earner, there is no difference between the government inflating the money supply, and a private entity doing it. Expanding the supply of dollars makes every other dollar less valuable than it otherwise would be.

In a growing economy, each dollar becomes more valuable unless someone inflates the supply of dollars. Whoever does inflate that supply seizes the value of the increased productivity. Under current monetary policy, banks do so more than fast enough to prevent dollars from increasing in value: they actually cause prices to rise during periods of economic growth that would otherwise cause prices to fall and the standard of living to rise.

The fact that there is additional material wealth ‘backing’, in some sense, all of the additional credit misses the point. There’s nothing immoral about lending money that one has earned. There’s nothing immoral about paying interest to encourage people to deposit their currency, and then lending out that currency that is held on a time deposit. The immorality is in creating the dollars out of thin air without first earning or borrowing them. The interest earned on the lending of the unearned is interest that rightly ought to have been paid to those who earned or borrowed the loaned-out amount.

At the end of the day, the fractional reserve system is a system for the massive, immoral, redistribution of wealth: from those who earn dollars to those who merely print them.

With a 100% reserve, the banks would have to earn or borrow the dollars they lend out. Lending to productive businesses would continue, but all wealth, including the banker’s, would be earned. There would still be risk, because even a time deposit needs to be honoured by the bank when it expires. The bank would pay for the use of the money deposited, and would profit if it loaned out money to sufficiently productive borrowers.

There would be no shortage of money as the economy grew because prices would fall over time, which means that, over time, less money would have to be borrowed for the same given purpose.

As for central banks: eliminating them, alone, would not make the fractional reserve system moral. In fact, it was the fractional reserve system that led banks to want to form a central bank, so that they could borrow currency from one another if they found themselves facing depositors who wanted to withdraw more currency than the bank actually had. Eliminate the government-owned central bank, and bankers will simply form a private one. Eliminate fractional reserves, and nobody will need one.

“In defense of fractional reserves”, by PortfolioManager1987

“Understanding Money and Banking, Part V: Inflation, the Gold Standard, and Fractional Reserve Banking”, by Paul McKeever

PortfolioManager1987 has posted a follow-up video on fractional reserve banking, largely in response to the comments I made to his first video on the subject. The video is mostly comprised of a reading from the book “Gold and Liberty” by Richard M. Salsman (I haven’t read Salsman’s book, but it sounds like an interesting read). In response to the follow-up video, I made the following comments:

Hi Paul McKeever,

I have a question. While I do agree with just about everything you say, I cannot figure out why you do not think the issue is, at least in part, about fraud. Why wouldn’t fractional reserve banking constitute to fraud? Isn’t it, essentially, the same thing as selling the same house to two different buyers simultaneously?

I only know of one argument against the claim that fractional reserve banking would constitute some kind of fraud, and it basically says that as long as the bank customers knows what is going on, and then goes along with it voluntarily, then it is not fraud. But to me the obvious counter argument to this is that it would only mean that the bank customers also are in on the fraud. They are, so to speak, accessories to fraud.

What say you?

PS: Love your youtube videos. Keep it up.

Thanks for posting this! I have argued the same idea myself (although most of what I have written is in Swedish). In particular, I have argued that “fractional” money issued by private banks is immoral for the same reason that inflation in general is immoral – and that it will have the same bad effects (although probably on a smaller scale).

There are, however, a couple of points I would like to mention (maybe you know them already):

It is not true that libertarians in general are for fractional banking. Those who follow in the footsteps of Murray Rothbard advocate a 100% reserve standard. (Those people are dead wrong on other things – as you probably know – but they are right about this.)

But neither is it true that all Objectivists are for a 100% reserve standard. (They should be, but unfortunately they aren’t.) I know this, because I have had to defend my own stand against other Objectivists. The argument I commonly hear is that since this “fractional money” – in a system without a central bank – appears on a free market, it cannot be fraudulent. (But that is precisely what it is!) Those people, by the way, seem to get their arguments from Richard Salsman.

As I said, you may already know all this. If not, I have told you now.

Paul, do I understand you right: Fractional reserve banking should be illegal?

I think there is a slight error here, carried over from non-free markets to free markets.

Would the above scenario occur if the government backed all dollars with an implicit guarantee, whether backed by gold or not? Yes.

Suppose, however, banknotes actually mean what their name is – they are notes, good for a certain amount of something (gold, lets say,) backed by the bank – not by the government, and not necessarily by any other bank.

Therefore, any fractional reserve system the bank chooses to adopt is:

1) Accepted by the people who deposit into the bank (in exchange for higher interest rates, being able to withdraw their money at any time, etc.,)

2) Only harms the bank itself or parties who agreed to that arrangement. If the bank lends out enough without backing that its health is called into question, their notes will be similarly devalued (or simply not accepted) to reflect the risk that the note will come up with nothing.

Therefore, not only is, say, Abc Bank NOT harmed by Xyz Bank’s fractional reserve system, but it self-regulates to whichever amount of fractional reserve is actually stable in the free market. Now, this might very well be 100% – but my point is that without a central government printing money, the problem is immaterial.

Without explicitly endorsing it, Reisman mentions in _Capitalism_ (free download on capitalism.net) that some think reserves would approach 100% in a totally free market. I think look up “fiduciary media” in the index.

Thanks for posting this. Originally I understood your argument for the most part, but I was unclear on where the crux of the justification was. This made things clearer, however I still have a couple questions.

If I understand right, it is a issue of individual rights, specifically property rights, correct? Do you think that the idea of fraud is relevant? After all in a way, isn’t that what they do when they loan money that for all intents and purposes doesn’t exist?

Wolfgang wrote:

“Paul, do I understand you right: Fractional reserve banking should be illegal?”

Yes. What makes it morally wrong for a central bank to create more central bank notes? Answer: creating more central bank notes – i.e., increasing the supply of dollars – devalues all of the dollars that existed before the additional dollars were added, and transfers the lost value to the newly-added dollars. Those newly-added dollars are UNEARNED capital, taken from those who earned the capital, without their consent. That same analysis applies to an increase of the dollar supply, whether dollars that are being increased are bank notes or bank credit.

Lending does not require an increase of the circulating money supply. I can lend you the $20 in my pocket, and charge you interest, without increasing the money supply. As examples, I can do it by:

(a) physically handing the $20 note to you, or

(b) doing two things: i) issue you an IOU payable to the bearer on demand, and ii) retain possession of the $20 note so that I can honour the IOU when it is presented to me for payment.

Banks issue more than $1 of credit for every dollar on deposit BECAUSE they do not want to have to borrow the money from a depositor, and pay interest to the depositor. Incidentally: that’s why savings accounts pay hardly any interest anymore (they used to pay more when reserve requirements were higher).

Carl Svanberg wrote:

I would argue that, for most individuals – specifically, for those individuals who do not know that banks create the credit that they lend out; those who do not understand fractional reserve banking – it is a fraud. However, there are those who do understand what the bank will be doing with their money if they deposit it and this latter group of people, when they make a deposit, consent to their money being used in that way. They knowingly accept the risk and consent to it so, for those people, fractional reserve banking is not fraudulent.

Some will argue: “Well, if everyone who deposits funds at the bank KNOWS that the bank is banking on a fractional reserve, then there is no fraud involved at all”. And, with that, I can agree (although I highly doubt there would ever be a situation in which people understood the banks to be creating the money they lend out, such that the hypothetical borders on the absurd). However, even in such an absurd situation – with every depositor knowing all about fractional reserve banking and consenting to the use of their money on the fractional reserve – it remains the case that theft is occurring via an expansion of the dollar supply. As an example, X, who is not even a customer of the hypothetical bank B (in which all depositors understand and consent to fractional reserve banking with their deposits), has his savings and wages devalued by B’s creation of additional dollars in the form of credit.

Thus, even if one could eliminate the fraud, the theft – the non-consensual seizure and redistribution of wealth – would remain.

I don’t think so. If all customers – depositors and borrowers – know that they’re involved in fractional reserve banking, I don’t think the bank is defrauding them, and I don’t think that they and the bank together are defrauding everyone else. Credit is, after all, money, and most payments are payments not of currency but of bank credit. So long as people reliably consent to being paid with credit, credit will continue to be money…and it should be.

I’m not advocating the elimination of credit. I have no objection to a bank holding a gold coin (for example) in its vault and issuing an IOU (i.e., bank credit) that people can pass from bank account to bank account as payment. I simply object to the bank paying/lending that gold coin out to someone while the IOU is still in circulation. So long as an “IOU, on demand, one gold coin” is in circulation and being used as payment, “one gold coin” had better remain in the hands of the person who issued the IOU.

Thank-you. I have more coming.

Per-Olof Samuelsson wrote:

I would say: on a much, much larger scale. Over 95% of the dollars comprising our money supply is not government-issued bank notes, but privately-issued bank credit.

Yes, I’m familiar with Rothbard’s argument and, for the most part, I agree with it. However, after advocating 100% reserves, he jumps to advocating “free banking” (in which there are no laws requiring reserves) with gold as currency (on the basis that the volume of gold cannot easily be increased). I would argue he favours free banking because, being an anarchist, he could not advocate a law requiring a 100% reserve requirement.

I have nothing against using weights of gold as money, but there are a few things that people tend to overlook which make it impractical at present. The most obvious is: at least in Canada, there is no law against using gold coins as money, but it isn’t money nonetheless, for one reason: it is not reliably accepted as payment for most goods and services in Canada. If people choose to use gold, fine, but I don’t think we ought to force them to do so via the creation of new laws.

Another problem is that there are so many laws preventing the free movement of people and capital that, until the globe is one big free trade, free-movement zone, imposing a gold currency standard in ones country could very well result in a situation in which the country literally had no currency. Google early Canada’s experience with “playing card” money, which was issued because wages were not being paid in specie, by France, to soldiers posted in Canada, and because the soldiers had nothing else to trade for food, tools, etc (not having farms etc.). In a world that prevents people from moving to the countries to which the money flows, some medium of exchange is needed in the de facto jail cell countries from which money is flowing.

Yep. Part of the problem is that they are told that the essential argument against fractional reserve banking is fraud; or that the real problem is a lack of assets backing new dollars. Both miss the point that the creation of more bank notes or bank credit redistributes not only wealth, but the ACCRUAL in wealth that would have happened for all dollar EARNERS had the dollar supply not been increased.

IchorFigure wrote:

That’s right. Capital must be earned (or borrowed from a consenting lender), not transferred via the creation of additional central bank notes or private bank credit.

If the borrower knows that the bank created the bank credit that he is borrowing, there is no defrauding of the borrower. And, in fact, both the bank and the borrower know that the bank’s credit will reliably be accepted as payment for most goods and services, so anyone who accepts payment, but who does not know the credit was created out of thin air, is not defrauded…but he has been stolen from via the inflation of the money supply that happened when that credit was created.

Brad Williams wrote:

I don’t think history supports that assertion. In fact, were it true, the private banks would never have needed – so quite probably would never have wanted and formed – a credit-issuing central bank.

Santiago Javier Valenzuela writes:

In your example, gold is a red herring. If the government’s policy was not to change the number of central-bank-issued dollars in existence, a bank could still issue credit specific to itself. And, in practice, that is exactly what banks do: each bank issues credit that must be honoured (in the form of central bank notes) only by the issuing bank.

But even if we use gold coins as the example currency, problems result. First, without a law requiring the banks to actually have the gold they’re promising to pay, banks can treat (and, historically, have treated) credit issued by other banks as though it is gold. For example, Bank A receives a $50 gold coin, lends out a $50 bank credit, which gets deposited in Bank B, which uses Bank A’s credit as an asset to back its own credit in the amount of $50, which gets deposited in Bank A, which uses Bank B’s credit as an asset to back its own additional credit in the amount of $50, and so on and so on. Expansion of the money supply –> devaluation of the dollar.

Second: most payments are now made not with physical currency, but with credit. With the increasing use of debit and credit cards, physical tokens could go the way of the dodo. Result: nobody would ever call upon banks to honour their credit with gold (or whatever is serving as currency). When nobody calls upon banks to honour credit, there is no run on the bank, so there is much less incentive to have low ratios of gold to credit. Consider that over 95% of the money supply is private bank credit, then consider whether that would be any different in a free banking situation when most people increasingly pay in the form of credit. Hint: it would, in practice, be more or less like Canada, which has no legal reserve requirement.

Third: in your example, banks are issuing credit in the form of physical tokens (bank notes) passed hand-to-hand, rather than electronic bank credit. Therefore, what you are really talking about is competing money supplies (each in the form of a bank’s own issued credit), not a single money supply. And your argument amounts to this: if one money supply proves to be worthless, people won’t accept it as payment, hence won’t borrow it. Well, that’s what we have right now, which is why my $20 Bank of Canada note can’t reliably buy me a Coke in Tennessee, and why some want to price oil in terms of Euros rather than in terms of US dollars.

Arguments about reserve requirements apply to a single money supply. Reserve requirements prevent a money supply from being a vehicle for non-consensual wealth redistribution.

Finally: when one of the banks in your example fails, the losers would include people who had neither a bank account nor a loan with the failed bank. If they got stuck with a note that the bank did not honour, and did not know that the bank was issuing notes on a fractional reserve when they accepted payment, they would have been wronged.

I have heard it suggested, by prominent objectivists, that fractional reserve banking is quite proper under certain circumstances. For example, in a completely private banking system, there would be no US reserve notes; all money would be issued by private banks. Therefore, if a bank chose to have a 100% reserve (with the requirement that funds are un-withdrawable) or 5% reserve, that would be the choice of that bank and the consequences would be reflected in that particular currency. As long as the Bank’s policy was disclosed, there is no issue of theft. E.g. If you buy a 5% reserve note from Bank A, there would be the implied disclaimer, “This is a 5% reserve Bank, and the corresponding consequences follow..”

I don’t know what would be the wisest policy, from the bank or customers point of view, but I don’t see any moral issue here.

Minroad wrote:

That’s like saying: “If all dollar notes had printed on them “the buying power of this note will gradually be transferred to banks over time, eventually leaving you with the buying power of a penny”, and a person voluntarily chose to be paid with such a note, he would have consented, so it would not be theft”.

In response to that I say: Yes, I agree, but (a) nobody is currently put on such notice, (b) such notes would immediately cease to have any value at all if one could instead be paid with a note that did not have its value gradually siphoned off by banks over time, unless (c) the government continued to insist that all taxes be paid with the constantly devalued money supply.

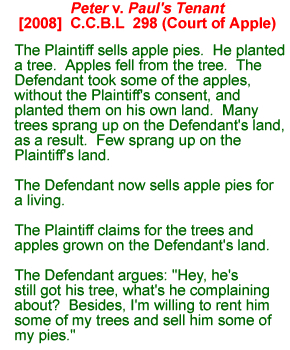

To use another example, it’s like Peter Schwartz’ mock libertarian argument (an argument that Schwartz uses to demonstrate the horror and irrationality of the libertarian understanding and application the concept of consent; see his “Libertarianism: the Perversion of Liberty”, in Ayn Rand’s The Voice of Reason):

Schwartz’ point is that the non-aggression principle – the correct understanding of when and how the concept of consent is applied – must be interpreted in light of the constraints imposed by Rand’s metaphysics, epistemology and ethics. Only a completely irrational person would consent to having the value of his savings constantly drawn away by banks so the argument about consent to theft applies only in a society entirely comprised of irrational people.

An ethical system of banking laws protects the rational person from looters and moochers. Legal policy ought never to be founded upon the belief that everyone is irrational. When a person earns and holds “a dollar” in his bank account, he holds a share of the entire supply of dollars. That share (that percentage) of the dollar supply is property and, when – by inflating the supply of dollars – someone decreases the percentage of the dollar supply represented by that person’s savings, that person’s property is being stolen. The law, accordingly, ought to make such theft illegal.

On the matter of Ayn Rand and her view on the essentials concerning the nature of inflation and why it is wrong, I refer you to this passage from Rand’s essay “Egalitarianism and Inflation”:

Paul McKeever: “I would say: on a much, much larger scale. Over 95% of the dollars comprising our money supply is not government-issued bank notes, but privately-issued bank credit.”

Is this true? I thought that the notes are issued by the Fed or other central bank and then lent out to the private banks.

But even if you’re right about this, the point is that the central banks function as a “lender of last resort”, so if a bank gets into trouble by creating too many bank notes, the central bank is always ready to bail the private bank out.

This is why I think that if there were no central bank, and private banks issued “fiduciary media”, a.k.a. “fractional money”, it would still create problems, but on a smaller scale than today. The risk of a bank run would make banks at least slightly cautious about issuing too many notes. This is of course not the system I advocate, but it would be better than what we have today.

I will return to some other issues later.

Brad Williams: “Without explicitly endorsing it, Reisman mentions in _Capitalism_ (free download on capitalism.net) that some think reserves would approach 100% in a totally free market. I think look up “fiduciary media” in the index.”

For the record: Reisman explicitly endorses a 100% gold standard. See “Capitalism”, p. 954ff. And there is a strong statement about the fraudulent nature of “fractional banking” on p. 958.

There is a discussion earlier in the book (p. 514) where he mentions the two “schools” regarding the legality of fiduciary media, without explicitly stating which of the two schools he himself adheres to. You may be misled by this. I, myself, was once misled, but I actually mailed Reisman and asked him about it, and he directed me to the pages later in the book.

As to Carl Svanberg’s question (nice to see you here, by the way!), I think it is almost a semantic nicety whether one calls “fractional banking” fraud or theft.

My own reasoning goes like this:

You probably know Ludwig von Mises’ point about inflation: that the newly created money always reaches some people before prices have risen, while others receive it after prices have risen. The first group stands to gain by inflation; the second group stands to lose. And the latter group is defrauded or stolen from, whichever term suits best.

But the same is true of fiduciary media issued by private banks. They will have an inflationary effect just as much as new money issued by the government or central bank. And there is the same time lag with prices. The person who borrows the fiduciary media from the bank can use the money to buy things before prices have risen. Others, who do not receive such loans, will have to pay higher prices later. The effect is actually the same: the second group is being defrauded or stolen from (again, whichever term suits best).

As George Reisman says on the page I referred to earlier:

“Thus if it occurs to anyone to argue that the banks’ customers are not victims of fraud because they clearly know and understand that their funds are being lent out, then the answer is that in that case they would be parties to fraud. Their fraud would be the attempt to make payment to others not with money or reliable warehouse receipts for money, but with claims to debt.”

(And Carl, of course, makes exactly the same point in his comment.)

Paul McKeever: “Yes, I’m familiar with Rothbard’s argument and, for the most part, I agree with it. However, after advocating 100% reserves, he jumps to advocating “free banking” (in which there are no laws requiring reserves) with gold as currency (on the basis that the volume of gold cannot easily be increased). I would argue he favours free banking because, being an anarchist, he could not advocate a law requiring a 100% reserve requirement.”

I’m not sure you’re right about this, but maybe you have read more of Rothbard than I have. As far as I know, he did think that fiduciary media (“fractional banking”) should be outlawed. And I have read an essay by him where he opposes the idea of “free banking” that includes fiduciary media.

But how he reconciles this with his anarchism, I don’t know, and I can’t figure it out.

An interesting discussion, Paul. But I don‘t see how the creation of fiduciary media — in a completely free market, without fiat money — can be inflationary.

Let’s consider a highly simplified system: there is no central bank, no fiat money, and we look at only one private bank and two customers, A and B.

We assume that this private bank has determined from a study of spending habits that a 5% reserve requirement is sufficient to cover demands for deposits. Thus, it feels safe in loaning 95% of any deposits on hand. (It goes without saying that all depositors must be made aware of this policy up front.)

So customer A deposits $100 into a checking account at this private fractional reserve bank. Customer B applies for and is granted a loan of $95, which is then credited to B‘s checking account. Now, it is true that when this occurs, there is now $195 on the bank’s books as checking deposits — the infamous “fiduciary media”. (And I understand that the process need not stop there — that provided he hasn’t spent it yet, 95% of B’s $95 dollars can be loaned to C, etc.. But I’m ignoring that because I don’t think it changes anything in principle versus the case of just 2 customers.)

However, the fact that there is $195 shown on the bank’s books as checking deposits does not mean that there is now $95 of “new money” that can be spent to purchase goods and services. The bank still has only $100 in its vault. If the two depositors behave as expected, customer A will spend $5 and B will invest his $95 dollars in some sort of venture for which he took out the loan — and no additional money — beyond the original $100 — will have been put into circulation to purchase goods and services.

Now what happens if customer A unexpectedly spends more than the $5 of his deposit? In reality, with many thousands of depositors, those that spend more than the average are balanced by those that spend less. However, if there is a net increase in spending such that the bank‘s reserves are disappearing, the bank will be forced to find additional money to cover it. It can do this by ceasing to make new loans or by attracting additional deposits or by borrowing from other banks. Or perhaps private deposit insurance would be sold to cover this.

But whichever way the bank utilizes to come up with the additional money, in a fully private system it is *existing* dollars — not brand new, out-of-thin-air dollars — that must be brought in to cover A’s unexpected spending. This must be the case since the bank has no power to create new dollars out of thin air.

Granted, A and B might write checks for the entire balance of their accounts. And when those checks are presented to the bank, it may not be able to find enough additional money to cover them. It might go bust. One could argue that under such a scenario, $195 got spent — $95 more than was originally deposited. But when the checks written by A and B bounce, those who were given the checks in payment will go back to A and B and demand their money or the return of whatever was sold to them.

Thus, it is not clear to me that the creation of fiduciary media — under *these* conditions — is inherently inflationary. Given that the bank can’t print new dollars — and there is no Federal Reserve there to loan them brand new dollars — the “fiduciary media” can‘t actually be spent beyond the amount of the original deposit — or beyond the amount of additional deposits and/or loans from other banks that can be arranged — it cannot artificially boost demand and raise prices. That’s why I don’t see how we can condemn *private* fractional reserve banking on principle.

Or am I missing something?

Of course, in a free market, with no “lender of last resort”, no central bank possessing the power to print up new fiat money, I can’t imagine that any bank would operate with the kind of thin reserves we see today. Perhaps *no* banks would choose to operate on a fractional reserve basis in a free market. But assuming everyone is told up front what the bank is doing, I see no basis for outlawing the practice.

I certainly agree that the current situation is inflationary; whenever it sees fit, the Federal Reserve injects new, additional dollars into the banking system (usually by purchasing Treasury securities held by the banks) which certainly dilutes the value of everyone’s money. That’s flat-out theft.

What’s more, the current situation is an insane house of cards ripe for an implosion. The banks in the U.S. have some $2.5 trillion dollars in checking deposits on the books, and only about $40 billion in actual cash on hand. I think this preposterously low level of reserves is an artifact of having a fiat money supply and a central bank with unlimited power to be “the lender of last resort”. I do not for a moment believe that free banking would see this kind of leverage of loans against reserves.

Your thoughts?

Michael Smith wrote:

There are two problems with that scenario; two things that make it impossible to evaluate the ethics of inflation:

Problem 1. The Money Multiplier Requires Two Banks When Reserves > Zero

Unless a bank is banking on a zero reserve, for the money multiplier to work, the scenario needs at least two banks. The reason: a bank does not treat its own IOU (i.e., bank credit issued by itself) as an asset, but it treats an IOU issued by another bank (i.e., bank credit issued by another bank) as an asset. So, to evaluate the argument about the existence and ethics of inflation, the example needs two banks: Bank X and Bank Y. Now, let’s make that change and see how it affects your explanation. For the purpose, I’ll use your words in bold, adding mine:

So customer A deposits $100 into a checking account at this private fractional reserve Bank X: in exchange for A’s $100 of gold coin, Bank X issues $100 of bank credit (an “IOU $100 of gold”), and we call that a “bank balance”.

At Bank X, customer B applies for and is granted a loan of $95, which is then credited to B‘s checking account: this means that B issues $95 of his own credit and gives it to Bank X which, in turn, issues $95 of Bank X’s credit, and hands it to B. In exchange for B’s IOU, which is not money, Bank X has given B its IOU, which is money (it is money because, unlike B’s credit, Bank X’s credit is reliably accepted as payment for goods and services). B pays Bank X interest because Bank X’s credit is money, and his own credit is not.

Now, it is true that when this occurs, A holds $100 of Bank X’s credit, B holds $95 of Bank X’s credit, and Bank X holds $100 of gold coin plus $95 of B’s credit. The money supply has been increased from $100 (all in the form of gold coin) to $195 (all in the form of bank credit).

B pays the $95 of Bank X’s credit to A (in exchange for some services), who deposits it at Bank Y (A likes having two banks, let’s just suppose): A gives Bank Y $95 of Bank X credit and, in exchange, he receives $95 of Bank Y credit.

B wants to borrow some more money. He goes to Bank Y, which holds back 5% and is willing to lend him $90: B issues and gives to Bank Y $90 of B’s credit and, in exchange, he receives $90 of Bank Y’s credit.

Now: A holds $100 of Bank X’s credit plus $95 of Bank Y’s credit; B holds $95 of Bank X’s credit plus $90 of Bank Y’s credit; Bank X holds $100 of gold coin plus $95 of B’s credit; and Bank Y holds $95 of Bank X’s credit plus $90 of B’s credit. The circulating money supply has been increased from $195 (all in the form of bank credit) to $275 (all in the form of bank credit).

And so on, with B borrowing next from Bank X again, then from Bank Y again, etc etc.; and with A depositing Bank X’s credits in Bank Y, and Bank Y’s credits in Bank X. If memory serves, with a 5% reserve of gold, the cycle will max out at the creation and simultaneous existence of $1,900 worth of bank credit, with only $100 of gold sitting in Bank X’s vault.

Problem 2. Theft Requires a Non-consenting Person, C

Let’s say that, while B is borrowing all of this money from Banks X and Y, and while A is saving it all in Banks X and Y, Person C is walking around with another $100 of gold coin in his pocket.

Consider what happens while B is doing all of that borrowing. Before A deposited his $100 of gold, there was $200 of circulating money in existence, all in the form of gold coin. When A deposited his gold, there was still only $200 of circulating money in existence: $100 in the form of gold, and $100 in the form of Bank X credit. A held 50% of the money supply, and B held 50% of the money supply. So far, so good.

Next, B and Bank X each issued, then exchanged, $95 worth of their own credit. This added $95 of bank credit to the circulating money supply: A held $100 of Bank X’s credit, B held $95 of Bank X’s credit, and C held $100 in gold. The circulating money supply had been increased from $200 to $295 (such that C’s $100 of gold is no longer 50% of the money supply, but has dropped to being about 34% of the money supply). The result? Prices rise. A beer that would have cost C $2.00 of gold coin will – perhaps six months after Bank X’s loan to B – cost him $2.95 of gold coin.

At the end of the cycle, when there is $1,900 of credit in the hands of A and B, and $100 of gold coin in the hand of C, the beer that used to cost C $2.00 of gold coin will now cost him $20.00 of gold coin…all due to inflation of the money supply (from $200 of gold, to $100 of gold plus $1900 of credit). Meanwhile, Bank X and Bank Y are collecting, from B, interest payments on the $1,900 of bank credit they created out of thin air and loaned to him.

What happened? C went from owning 50% of the money supply to owning 5% of the money supply. Where did the other 45% of the money supply go? To Banks X and Y, which created $1,900 of money in the form of unbacked credit. C was robbed of 45% of the money supply, which was transferred to the banks who obtained it by creating credit that was not backed, dollar for dollar, by gold.

Had there been a 100% reserve requirement, Banks X and Y would have had to encourage C to deposit his gold with them so that they could lend not more than an additional $95 of bank credit to B. And, with a 100% reserve, A and C would not have the right to spend the $100 that they had deposited with (i.e., loaned to) banks X and Y until a pre-agreed time had passed (by which time, B would be required to have repaid all of the credit he borrowed from Banks X and Y). The total money supply would, at all times remain $200, so price changes would not be the result of increases or decreases of the money supply…there would be no “inflation”, as that term is properly defined, unless productivity decreased.

Per-Olof Samuelsson wrote:

I could be wrong about Rothbard, but he seems sympathetic to free banking at times. See his What has Government Done to Our Money? starting at page 42.

Per-Olof Samuelsson wrote:

The Fed creates federal reserve notes, which the private banks use to back many times more dollars in the form of credit. Think of the fed’s notes as a replacement for gold, and think of private bank credit as a promise that “IOU the same fed note that is also, simultaneously, owed by my bank, and by other banks, to about 18 other people”.

Paul McKeever: “The Fed creates federal reserve notes, which the private banks use to back many times more dollars in the form of credit. Think of the fed’s notes as a replacement for gold, and think of private bank credit as a promise that ‘IOU the same fed note that is also, simultaneously, owed by my bank, and by other banks, to about 18 other people’.”

Yes, but this puts the blame squarely on the Fed. The point I was trying to make is that with free banking, but no legal injunction against fiduciary media, there would be no central banking bailing out an irresponsible private bank, and that would put some check on inflation. As I said, this is not ideal, but it would be better that what we have today.

It is also worth mentioning that in today’s situation, private banks hardly have another choice than following the Fed. Typically, the Fed creates an interest rate that is below what would prevail on a free market. Then, if a private bank were to use the higher interest rate rather than the Fed’s, people would not borrow from that bank. It is not the individual private banks that are to blame here, it’s the central banking system.

(The solution, of course, is to get rid of the Fed and other central banks once and for all. But – well – this will take some time…)

Btw, I will check up your Rothbard reference later. I may not have time today, but there is another day tomorrow.

Paul McKeever: “Yes. What makes it morally wrong for a central bank to create more central bank notes? Answer: creating more central bank notes – i.e., increasing the supply of dollars – devalues all of the dollars that existed before the additional dollars were added, and transfers the lost value to the newly-added dollars.”

Doesn’t the same hold for the production of all goods and services? If I start producing cars it will lower the value of the existing cars. It seems like all production is immoral…

Per-Olof Samuelsson wrote:

You’ll get no argument from me re: getting rid of a credit-issuing central bank (though one still needs a clearing house among banks).

However, the fact that a free banking system (sans credit-issuing central bank) would reduce inflation does not mean that a 100% reserve law is wrong. Inflation is theft, and it is ethically right for the government to use force to prevent and punish such theft, even if getting rid of the central bank would reduce theft.

As for blame: I don’t buy the argument that the central banks are the only ones to blame. First: those banks were set up by the private banks originally (which is why, incidentally, it is fantasy to suppose that getting rid of state-owned central banks would eliminate central banking: the private banks would just set up a private central bank, as they are want to do).

Second: the fact that you CAN borrow from the central bank does not mean that you HAVE to do so. No bank is REQUIRED NOT to have a 100% reserve. They freely choose to lend out more credit than they have a reserve for. Ethically, they are every bit as guilty as the central banks – which they set up, initially – that facilitate and secure the system of theft.

And, while we’re passing around blame: every government that does not pass a law against fractional reserve banking is, as I see it, failing to do its duty.

Paul McKeever: I *do* think that there *should* be a law demanding 100% reserves. My point was that in today’s situation, banks who do not follow the Fed’s interest rate will get no customers. And one cannot morally blame anyone for not doing the impossible.

Suppose for example that the interest rate according to actual market conditions would be 5%, but Alan Greenback – sorry, Greenspan – sets a rate of 1%. A bank which sets its interest rate too far above this 1% would not be able to find customers willing to borrow from it. A bank acting morally would go bankrupt. (Actually, I think this is an example of morality ending where a gun begins.)

If we managed to get rid of the Fed, the situation would be different. In that situation, a bank who does not adhere to a 100% reserve *would* be morally to blame.

Per: “Doesn’t the same hold for the production of all goods and services? If I start producing cars it will lower the value of the existing cars. It seems like all production is immoral…”

There is one hell of a difference between producing cars and “producing” worthless paper money. I wouldn’t call the latter “production” in any serious sense of the word. It is simply counterfeiting.

Another Reisman quote may be in place here:

“It should be understood that everything I have said in connection with the subject of fraud entailed in fractional-reserve banking applies to a context in which the establishment of a 100-percent-reserve gold standard would be a real possibility. It is pointless to accuse either banks or their customers of fraud in connection with fractional-reserve banking in a context such as the present, in which the overwhelmingly greater fraud exists of the government’s creation of a monetary standard that is utterly nonobjective and arbitrary, namely, the fiat-paper standard.” (“Capitalism”, p. 958.)

Paul McKeever writes:

[…]

“Now: A holds $100 of Bank X’s credit plus $95 of Bank Y’s credit; B holds $95 of Bank X’s credit plus $90 of Bank Y’s credit; Bank X holds $100 of gold coin plus $95 of B’s credit; and Bank Y holds $95 of Bank X’s credit plus $90 of B’s credit. The circulating money supply has been increased from $195 (all in the form of bank credit) to $275 (all in the form of bank credit).”

No bank can legitimately loan out money on the credit of *another* bank, but only against its own actual deposits – it is only these deposits of actual money that constitute that bank’s reserves. To the extent banks are able to do otherwise today is the flaw for which you are properly opposed, but that is NOT what fractional reserve is or should be, it should be limited to *actual* deposits in an individual bank.

When my bank loans $95 of my deposits to B, and B deposits that IOU in Bank B, Bank B cannot use that IOU as actual money to back its own fractional reserve – and therefore cannot loan out a penny (let alone $90) against it – *precisely because it is an IOU against deposits in another bank* not an actual deposit of money in Bank B.

For Bank B to issue loans against the reserves of Bank A is indeed be fraud and should be dealt with accordinly, rather than abetted by government. In fact it essentially constitutes a ponzi scheme with an inevitable result of most IOUs being worthless.

There is no fraud and there is no inflation caused by genuine fractional reserve lending. The whole point of fractional reserve is that it is using statistics to determine a safe fraction – that fraction of deposits that normally sits idle. Thus it averages out that money loaned out equals money not in demand by its depositors. Banks keep that in balance by a number of means: reducing loans and/or increasing loan rates if reserves get close to the minimum, and increasing interest paid on deposits to attract more *actual* deposits (again IOUs issued by other banks DO NOT count). This keeps it perfectly moral and consistent with capitalist and Objectivist principles and $100 deposited remains only $100 in fact.

Also, in a free market, no reputable bank would work on a 5% reserve or anything close to it. That is only the case due to *government intervention* – taxpayers back that reserve. The current meltdown is a very clear consequence of that interference. No part of the current meltdown was caused by *free market* fractional reserve banking.

W. Niddery wrote:

Well, in reality, that is what fractional reserve banking does involve, and it is what “fractional reserve banking” is regarded to be. Advocates of fractional reserve banking – even most of those who stick the words “free market” in front of the words “fractional reserve banking” – regard IOUs from other banks as money – and therefore a legitimate part of a bank’s reserves – because, in fact, it is money: money is any property that reliably can be exchanged for other property or for services. The problem, of course, is that credit is not a tangible good of relatively unchanging quality and quantity (see Rand’s “Egalitarianism and Inflation”); it is not “money” by Rand’s tighter definition; it is not “money” in the sense meant by advocates of gold money.

A 100% reserve requirement requires all credit to be backed by currency (i.e., at present, central bank notes; formerly, gold).

I understand the system you are talking about. Essentially, it is a 0% reserve system with a stipulation that there be a law prohibiting banks from treating bank-issued credit as reserve.

That sentence is false on its face. Fractional reserve lending – even by your own definition – involves banks issuing credit in excess of reserves.

For example, imagine that the entire money supply consists of ten $10 gold coins: the money supply is $100. A brings five $10 gold coins to the bank and trades them for $50 of bank credit (i.e., he makes a “deposit”), such that he can present the credit to the bank at any time in the future and demand payment in gold. Both before and after the deposit, there is $100 of money in circulation: before the deposit, there was $100 in the form of gold coin and, after the deposit, there was $50 in the form of gold and $50 in the form of credit. B comes to the bank and borrows $50 of credit from the bank: the money supply (i.e., the dollars in circulation) will have increased from $100 to $150: $50 in the form of gold coin, and $100 in the form of credit. Now, it turns out that that $50 of gold coin (which is not on deposit in the bank but is, rather, in circulation) is all sitting in a sock owned by C. Before the bank created $50 of credit and loaned it to B, the money supply was $100: C held 50% of the money supply. However, after the bank created $50 of credit and loaned it to B, the money supply was $150: C held 33.3% of the money supply. Where did C’s missing 16.7% of the money supply go? To the bank, when it printed the extra $50 so that it had something to lend to B. How much of the interest earned on that 16.7% (which was loaned to B) goes to C? None. The bank is earning interest on the money that C earned; money that the bank did not earn, but merely printed into existence.

It gets worse. As a result of the bank inflating the money supply by 50%, prices climbed by 50%: inflation caused prices to increase by 50% (note, most economists, today, call the increase in prices “inflation” but, originally, the increase in the money supply was the thing referred to as “inflation”). Before the bank issued that exta $50 to B, C could have bought a tank of gasoline with his $50. After the bank issued the extra $50 that it loaned to B, C can buy only 2/3rds of of a tank of gasoline with his $50: a full tank now costs $75, all because the bank issued an extra $50 in the form of credit (which it loaned to B).

So, even under the “free market fractional reserve” system you propose, (a) there is inflation, such that (b) there is theft.

Now some will say that I’m telling only half a story. They will say that if B uses the $50 to produce something, the economy will grow. That’s certainly possible, so let’s assume a fact scenario where it is true. Specifically, let us assume that the economy grows by 50% after B borrows the extra $50 from the bank to put to a productive use. As a result, there are more goods and services competing for everyone’s money. And, let’s assume, the result is that – both before and after the bank increases the money supply – C’s $50 will still buy him a full tank of gas. “No harm, no foul” says the fractional reserve advocate. Except for one thing. It remains that what made the loan to B possible also caused C no longer to own 50% of the money supply. In other words, whether or not the loan to B grows the economy, it remains the fact that the bank’s inflation of the money supply caused 16.7% of the money supply to be transferred from C to the bank.

What if there had been a 100% reserve? Well, then the bank could still lend B the $50 that A deposited initially, but, while that money was on loan to B, A would have no right to demand that the bank pay him $50 in gold (i.e., he’d have no right to withdraw his $50 gold coin while the $50 was being loaned to B). B would agree to repay the loan within one year, and A would agree that he could withdraw his gold coin only after 1 year had passed. Now, B goes out with the $50 and produces the same goods he produced in the first example. As in the first example, he increases the size of the economy by 50%. However, the money supply, all the while, has remained $100. Both before and after the bank makes the loan to B, C holds 50% of the money supply in his sock. The lending of money to B is non-inflationary, and it does not cause prices to rise. And consider the effect for C. As a result of B having grown the economy by 50%, there were more goods and services competing for everyone’s money, so prices decreased by 33.3%. Therefore, after B has borrowed the money and grown the economy with his productive efforts, C can fill his tank for $33.33, and still have $16.67 left over to pay for a nice night out with Mrs. C. As the economy grows, and the money supply is left unchanged, everything gets less and less expensive. Every person must continue to improve his productivity or else he will see the value of his labour drop over time as the economy grows. Those who continue to improve their productivity will find their standard of living rising. Those whose productivity does not change will find that they can always buy the same things they used to buy.

The above, of course, is a very coarse generalization, but it serves the purpose of demonstrating (a) that even a “free market fractional reserve” system would be inflationary and would involve a non-consensual transfer of wealth from C to the bank (i.e., a theft), and (b) that a 100% reserve system would ensure that theft did not occur, and that all money is earned.

Paul McKeever: “I could be wrong about Rothbard, but he seems sympathetic to free banking at times. See his What has Government Done to Our Money? starting at page 42.”

I looked this up, and I don’t see that he endorses fractional reserve banking at all. He writes:

“The dire consequences of fractional bank money will be explored in the next chapter. Here we conclude that, morally, such banking would have no more right to exist in a truly free market than any other form of implicit theft.” (P. 50.)

And later on the same page:

“If fraud is to be proscribed in a free society, then fractional reserve banking would have to meet the same fate.”

He does have a long reasoning to the effect that those “dire consequences” would be lesser with free banking (if FRB were permitted) than what we have today with a central bank. Well, this is my view, too. It would not be perfect, but it would be better than what we have today. But this does not mean an *endorsement* of FRB, neither from Rothbard, nor from me. We should strive for the best and not be satisfied with the second best.

I don’t understand Mr. Niddery’s reasoning. If “$100 deposited remains only $100 in fact”, then what is “fractional” about it?

Paul McKeever writes:

“B comes to the bank and borrows $50 of credit from the bank: the money supply (i.e., the dollars in circulation) will have increased from $100 to $150: $50 in the form of gold coin, and $100 in the form of credit.”

Obviously this is the crux of the disagreement. Loaning – issuing an IOU for that $50 – does not increase the money supply, it is a loan of that *actual* $50 on deposit and sitting idle (and of course they would not lend out the entire $50 anyway, only a *fraction* of that).

Your only real objection is due to the ability of A to come and demand his $50 and he will get it even while the same amount is on loan. If A were the only, or one of a very few, customers then there *would* certainly be a problem – the bank would not have sufficent funds to cover it. But that also demonstrates very clearly that the money supply has not increased and the bank has not “created” money, since in that case the bank would go broke if it were not able to recall the loan from B in order to make good on A’s claim, or borrow from elsewhere. If they default, then A has been done an injustice to be sure, but the original money supply is perfectly intact.

Of course no viable bank has so few customers. But also, the number of customers they have directly affects the actual fraction of deposits they must keep on reserve in order to make sure thay *can* always meet demands. A very small bank would require a very high reserve, possibly even 100%. Large banks can safely have lower reserves. It’s easy to demonstrate why (and also demonstrate a 50% reserve):

A deposits $50. Bank loans $25 of that to B. C also deposits $50. Bank loans $25 of that to D. A comes in and demands his entire $50. Bank *has enough reserve to make good* and hands A his $50. Total amount in circulation: $100, no more, no less. That 50% reserve allowed the bank to honour a demand from one of its customers even though it had loaned out a fraction of it.

At this point of course, they are in trouble if C now wants any part of his $50 deposit, they have $0 left on reserve and would either have to call in $50 worth of loans to others, or borrow from another bank. But in either case it *again* demonstrates that no *new* money has been issed, there is still only the original $100 total deposits circulating. A bank with 1000s of customers can cover actual demands quite easily precisely because, barring some panic and subsequent run on deposits, the bank can depend on some *fraction* of those deposits to always be on hand.

It is exactly the same reason insurance works – premiums from all customers are pooled, allowing the claims of some to always be covered. If everyone died, got sick, had accidents, all at once, clearly the insurance company would go broke as well, but it also clearly doesn’t happen, barring only the worse case catastrophes. Fractional reserve banks are not *creating/inflating* money any more than those insurance companies are.

To Per-Olof: As I demonstrate here, “fractional” refers to the portion of deposits a bank keeps on reserve in order to be able to honour expected normal demands of its depositors.

The phenonmenon of such low fractions such as 5% being used is *only* a result of government imposing deposit insurance, forcing low interest rates, allowing bailouts, and actually inflating the money supply, none of which takes place in a free market.

Now as to the currently accepted meaning of fractional reserve – that it includes the idea that a bank can count as part of its reserves IOUs that are already being backed by the reserves of another bank, and so on down the line: I realize, in writing my own example here, that it may not, in fact, be a problem *anyway* and might actually be perfectly legitimate (i.e. I may have to amend my own previously stated position on this – but I do need to think this through some more yet before committing to it).

The reason is, again, due to the nature inherent in the pooling of resources from many. Extending my example further, if B deposits the $25 IOU he was loaned in Bank X, and X counts that as a real deposit and thus loans out $12.50 of it to E, it is still subject to the same pooling, and the safety of that. It is true that all *potential* claims on my original $50 could exceed that $50, but the whole point is that, on average, *actual* claims at any point in time will *not* exceed that original $50. And due to pooling, it is not a problem for individual cases to do so because they are easily covered by other deposits not currently being demanded.

W Niddery writes:

Let me rephrase your answer before I respond to it. You are saying that, because the $50 of gold is in the vault, creating $50 to lend to B does not increase the money supply.

That’s false. Here’s why. Start with $100 of coin being the entire money supply. B holds $50 of gold coin, and so does D. B “deposits” his $50 of coin at the bank: this means, legally, he exchanges $50 of coin for $50 of bank-issued credit (it is NOT the case that the bank takes his gold, puts it in a vault, and gives him nothing in exchange). C then borrows, say, $49 more bank-issued credit. There is now $50 of gold coin in the vault, another $50 of gold coin in D’s pocket, $50 of bank-issued credit held by B, and $49 of bank-issued credit held by C. Excepting the $50 of gold coin that is sitting idle in the bank’s vault, the money supply has increased from $100 to $149 because the bank issued $99 of credit with respect to the same $50 of gold coin reserves. That is an expansion (i.e., an inflation) of the money supply. The result of issuing $99 of credit on a $50 reserve of gold coins is that the value of all dollars, including the value of D’s gold coins, has been decreased. D used to be able to get a full tank of gas for his $50. Now, he can only get 2/3rds of a tank for his $50.

If you haven’t discovered him already, you may be interrested in the works of Thomas Sowell. He’s a wonderful pro-capitalist economist and has written a small library of books.

[…] McKeever presents Banking and Morality: 100% Reserve versus “Fractional” Reserves posted at Paul McKeever, saying, “this blog post, made in response to a vlogger who advocates […]

Paul,

I know I agree with almost everything that you write here on this subject, and as an advocate of Soddy and Fisher, I see a lot of commonality.

I am not sure I am in total agreement, but I hoped you could address the matter of interest.

Take any Base money supply amount.

With FRBanking any increase in the money supply, and therefrom all money in circulation, is lent into existence, securing a loan amount (A) with a contract and PN.

Between the loan contract and PN is an obligation to repay the interest on that loan along with the principal(A + B).

If ALL money in a debt-money system comes into existence as a debt, and if all loans require the repayment of a sum greater then the principal amount, then from where does the interest payment money come into existence?

This is partly covered in the Zeitgeist Addendum video, Part 1.

Steven Lachance identifies the unpayable interest as the achilles heel of the debt money system, if you check it out here.

http://www.financialsense.com/fsu/editorials/2005/1212b.html

So, we need a new money system, and, of course it must be based on full-reserve banking.

Your thoughts, please, if you are still posting on this subject?

Or write to me at my email address.

Hi joebhed:

You are referring to a commonly-made error. The error was – as I see it – most famously and influentially propagated by the Social Credit folk…especially, among them, the “Pilgrims of St. Michael” in Quebec, Canada (also known as the “White Berets”). Their main vehicle is a newspaper called “The Michael Journal” which – last I saw a copy – arguably and disgracefully portrayed bankers as devils, freemasons, or jewish people (or some combination of the three). That’s a side-issue, but the fire used to foster such anti-Semitism was none other than the very error that you are referring to: the idea that the debt money is a trick, invented by bankers, so as to foreclose on everyones property and take over the world.

Here’s a link to one of the most famous/influential publications used to propagate the “but the interest cannot be repaid” myth:

http://www.michaeljournal.org/myth.htm

(re the anti-Semitism I refer to earlier, note the appearance of the banker, as opposed to the islanders).

Now, I give you that comic as a reference because the comic actually makes it easier to understand the flaw in the notion that “the interest cannot be repaid”.

The key passage in the comic is:

The flaw is as follows.

First, note that the banker is not trading on the Island: “And it’s money you’re asking for, not our products.” He is not participating in the economy. He might just as well be visiting from Saturn when he drops of the money, disappearing, and visiting again when he comes to collect it all plus interest. But that’s not how things work in the real world. Bankers are human beings, just like everyone else. They don’t just lend out money: they trade the interest they earn for the goods and services offerred by the very people to whom they lend money, and those people use their profits to pay interest to the banker and to pay down debt over time. Bankers lend money to grocers, and clothing retailers…but they also buy groceries and clothing with the interest that they earn on the dollars they loan out. They use some of the interest to pay employees – – receptionists, secretaries, tellers, cleaners, security, etc. – who buy groceries and clothes. They pay some of the interest to power companies to light and cool the bank; to natural gas companies to heat the bank…and those power and gas companies pay employees…who buy groceries, and clothing, and gas, and electricity, etc.

Second: note that the only economy available to the banker in the story is the one on the island. There isn’t some other economy somewhere else, where the banker can buy groceries, clothing, heat, electricity, a house, etc.. So, somehow, without producing anything all year long, and without obtaining anything other than a shelter from his borrowers, he somehow eats, stays warm, gets from one place to another etc.

Third: note that, in the story, the banker returns and expects the simultaneous repayment of the *entire* money supply come year’s end. That is never the case in a real economy. People generally pay in installments of interest and principle but, more importantly, they do not repay all of their loans simultaneously. And, if all of the money were repaid: there would be no more money, because debt ceases to exist when it is repaid. The entire story is silly…and the notion that there isn’t enough money to pay down principle plus interest is silly for the same reasons: it makes the same false assumptions made in the story.

The bottom line is that interest payments do not remain in the banker’s hands: they go back out into the economy because he uses the interest payments to buy labour and goods. For that reason, it is always possible for a debtor to repay his debt and his interest.

[…] recently received a question from a reader concerning my post of October 20, 2008, entitled “Banking and Morality: 100% Reserve versus “Fractional” Reserves“. It reads as follows: Take any Base money supply […]

A friend sent me your video on fractional reserves. These are my comments

Watched this video by your blogger – who has no expertise on the subject.

https://blog.paulmckeever.ca/2008/05/28/inflation-the-gold-standard-and-fractional-reserve-banking/

1. He is right about gold – you can have inflation with it.

2. He is right about 100% reserves – you could have that. But he forgets you would need much more cash. Think about all the assets people own – they are far greater than their income. With his system, you would need enough cash to convert all those assets, houses, buildings, jewelery … to cash.

3. He is wrong about money – he equates cash to money. All money is not cash, but all cash is money.

4. He is wrong about a run on the bank. If everyone insisted on having their money in the form of cash, the central bank could print it, and lower the reserve ratios.

He never accounts how he would increase the money supply. Central banks are wholesalers of money. They can buy a bond from a bank with government created cash, and get interest for it. They can sell bank the bond and get cash for it. One adds cash to the system and one takes it out of the system. The latter is what the Fed has in mind to reduce reserves.